We’ve moved to a nicer and better location on Greater Mekong Research Center’s website. You can follow us through this link.

Can an English law-style ‘floating charge’ be granted as security over assets in Cambodia?

A “floating charge” under English law is a creature of equity that allows creditors to take security over the fluctuating assets of a debtor without hindering the debtor’s capability to sell and dispose of their assets until an event of default occurs.

The Collins Dictionary of Law (2001) describes a floating charge as follows:

a security created by a company by debenture (in Scotland, a floating charge) over its whole assets and undertaking for the time being. The point of this form of security is that the company may continue to conduct its business, disposing off some assets and acquiring others without having to obtain the consent of the debenture holders for each disposal. In the event of a default, the charge crystallizes and becomes fixed and enforceable over the assets held at that time.

A floating charge is unique to common law jurisdictions. In civil law countries, lenders often take and perfect their security interest in individual assets.

The Civil Code of Cambodia (2011), drafted with the assistance of the Japan International Cooperation Agency, does not recognize floating charges on assets, however provides for creating real security rights through conditional transfer of property, which may be used by lenders to take security over changing assets of a debtor (‘transfer as security’).[1] The Civil Code additionally provides that real rights (including security rights) vested in movable and immovable property situated within the territory of Cambodia may not be created except as permitted under the Code or by special legislation[2] (jus cogens)[3]. At the same time, the Law on Secured Transactions, that puts together an “in-substance” system, standing in contradistinction to the Civil Code’s “form-based” regime, allows for the creation of a UCC Article 9-style ‘floating lien’ security package on the assets of the debtor. This security interest functions similarly to a floating charge under English law, however has some key differences which I shall discuss in another blog post.

That being said, agreements granting security interests in properties located in Cambodia, in a manner not in conformity with the Civil Code, the Law on Implementation of the Civil Code, the Law on Secured Transactions, and other applicable laws, shall be considered void, even when specified as governed by foreign law.

1 Article 888 of the Civil Code of Cambodia (2011)

2 Article 131 of the Civil Code of Cambodia (2011)

3 Roman legal literature distinguished between rules of jus cogens, which could not be derogated from by the parties, and jus dispositivum, which could be set aside by contrary agreement.

Accessing the Cambodian Constitution

Did you know that the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia can be accessed on Wikisource? Wikisource is a free library of source text and a sister-project of Wikipedia hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation based in San Francisco, CA.

Three years ago, I had trouble finding a copy of the Constitution in HTML/plain text format. Most of the copies available online at that time were in PDF format, some of which had issues with translation while others were in image-format making the text non-searchable. This is when I decided to upload the Constitutional Council’s English translation of the document on Wikisource.

This is the latest version of the Constitution, which contains the most recent amendment that elevates the National Election Commission to the status of a constitutional body from that of a statutory one.

The Law on Copyrights and Related Rights (2003) categorically excludes the constitution, legislation, sub-legislation and regulations from protection under the statute. These texts and their translations into other languages fall directly into the public domain.

Article 10 of the Law on Copyrights and Related rights

The following works shall not fall under any protection conferred by this law:

(a) Constitution, Law, Royal Decree, Sub-Decree, and any other Regulations;

(b) Proclamations (Prakas), decisions, certificates and other circulars issuing instructions issued by state organizations;

(c) Court decisions and other court warrants;

(d) Translation of those materials mentioned in the preceding paragraphs [a], [b], and [c] of this article; and

(e) Idea, formality, method of operation, concept, principle, discovery or mere data, even if expressed, described, explained or embodied in any work.

Choice of law and mandatory provisions

These questions often come up frequently during our discussions with investors and their legal counsel: (1) whether their contractual relationships in Cambodia can be governed by foreign law, such as English law or Singapore law?; and (2) will Cambodian courts enforce such agreements?

Brief Background

The Kingdom of Cambodia is a constitutional monarchy that has been influenced by the continental civil law tradition. The Constitution recognizes and provides for the implementation of a legal order that is conducive for the functioning of the “market economy system”1, recognizing the right of individuals to “freely sell and exchange their products”,2 providing for protection of private property rights,3 while placing restrictions on the State’s power of expropriation.4 The Constitution, however, also obliges the State to regulate the market in order to achieve “a suitable living standard for citizens”.5

The drafters of the Civil Code (2011) sought to bring about an equitable balance between the rights of the individuals and the State’s obligation to secure the rights of the citizens by providing for the principle of “private autonomy”,6 respecting the free intentions of the transacting parties, including legal persons, and at the same time prohibiting the “abuse of rights”.7 The Civil Code also emphasizes that all rights shall be exercised and all duties performed in “good faith”.8

(1) Whether their contractual relationships in Cambodia can be governed by foreign law, such as English law or Singapore law?

Individuals and legal entities can choose to have the law of a foreign country govern their contractual relationships in Cambodia even in the case of purely domestic transactions, subject to some qualifications. Transacting parties generally retain a high degree of flexibility to formulate their contractual relationships in the manner they deem suitable, with minimal interference from the State. Exceptionally, the law provides that in the case of any acts or agreements repugnant to Cambodia’s public policy (‘public order’ or ‘good customs’),9 the choice of foreign law may be vitiated if this dispute is heard in Cambodia. Similarly, ‘mandatory provisions’ (jus cogens) as specified in the Civil Code (2011) also preclude and supersede choice of law provisions applying foreign law, in favor of Cambodian law.

For example, the Constitution mandates that only natural persons and legal entities of Khmer nationality are eligible to exercise the right to ownership of land within the territory of Cambodia.10 The Land Law (2001) gives effect to the aforesaid provision of the Constitution and further clarifies that in respect of legal entities, only those entities with fifty-one percent (51%) ownership interest with natural persons or legal entities possessing Khmer nationality shall be eligible to own land within the Kingdom. The law further states that, in the case of legal entities such as limited liability companies, only the ownership structure reflected in the Memorandum and Articles of Association (or the articles of incorporation) registered with the Ministry of Commerce (MoC) shall have validity under the law, and any other private agreements among the shareholders to the contrary shall be deemed null and void.11 All legal provisions pertaining to real rights in movable and immovable property situated in Cambodia are generally understood to be mandatory provisions.12

Further, another illustrative case is that of the Labour Law (1997), which governs the relationship between employers and employees resulting from employment contracts to be performed within the territory of Cambodia.13 The section on ‘public order’ contained therein expressly prohibits the derogation of the provisions of the statute. It states that “all rules resulting from a unilateral decision, a contract or a convention that do not comply with the provisions of this law or any legal text for its enforcement, are null and void.14 While this requires strict adherence to the letter of the law, it does not prohibit the grant of benefits greater in magnitude than what has been provided for in the statute.

Additionally, other mandatory provisions contained in the Civil Code include: (i) provisions concerning declarations of intent15 and legal capacity,16 (ii) prohibition against forfeiture agreements,17 and (iii) the limits placed on the interest rates.18

(2) Will Cambodian courts enforce such agreements?

Our understanding with regard to the prevailing practice within the Cambodian judiciary is that the local courts will generally not apply foreign law for determining controversies and adjudicating disputes. Cambodian law does provide for the recognition of legal instruments issued by foreign governments,19 and where necessary, it treats foreign law as ‘fact’ requiring evidence to establish proof.

Risk mitigation

In the event you determine that having foreign law govern your contractual relationship comports with your legal strategy, we would recommend that you ideally choose commercial arbitration as the primary dispute resolution mechanism. As a signatory to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the “New York Convention”), Cambodia is bound under the terms of the convention to enforce foreign arbitral awards. Correspondingly, the Commercial Arbitration Law (2006) also lays down the process with which domestic arbitral awards are enforced.

At the same time, in the absence of a treaty conferring jurisdiction on to foreign courts and guaranteeing reciprocal respect for the Cambodian judiciary among other conditions, orders and judgments of foreign courts will not have the force of law and may not be enforceable.20 To the best of our knowledge, there are no treaties in existence that confer recognition and jurisdiction to the acts and decisions of the courts of a foreign country in Cambodia.

If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to drop me a message either in the section below or contact me via email: anirudhsbh [at] gmail [dot] com.

Anirudh S. Bhati is an India-qualified lawyer based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. This text simply comprises of research and personal opinion, and should not be construed as legal opinion or advice.

1 Article 56 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1993)

2 Article 60 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1993)

3 Article 50 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1993)

4 Article 44 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1993)

5 Article 63 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1993)

6 Article 3 of the Civil Code (2011)

7 Article 4 of the Civil Code (2011)

8 Article 5 of the Civil Code (2011)

9Article 354 of the Civil Code (2011)

10 Article 44 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1993)

11Article 9 of the Land Law (2001)

12Article 131 of the Civil Code (2011)

13Article 1 of the Labour Law (1997)

14Article 13 of the Labour Law (1997)

15Chapter Two: Declaration of Intention and Contract of the Civil Code (2011)

16Chapter One of the Civil Code (2011)

17Article 827 of the Civil Code (2011)

18Article 585 of the Civil Code (2011)

19Article 155 of the Code of Civil Procedure (2006)

20Article 199 of the Code of Civil Procedure (2006)

Book Launch: Cambodian Constitutional Law

I had the pleasure of attending the launch of a book produced by Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) on ‘Cambodian Constitutional Law’ this evening at the Raffles Le Royale. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung is a German organisation that is affiliated with the Christian Democratic Union, and has been deeply involved with facilitating legislative and political reform in Cambodia.

Dignitaries present included HRH Mr Sirivudh Norodom, member of the Constitutional Council, and Mr Hang Chuon Naron, the Minister for Education, Youth and Sports.

Note: the book is available for download on their website.

The sceptre of Brahma

The Cambodian Criminal Code is called “ក្រមព្រហ្មទណ្ឌ” (क्रम ब्रह्म दण्ड, /kram prum toan/), meaning ‘the Code of Punishment by Brahma‘. The term “ទណ្ឌ” (दण्ड, /toan/) which means ‘punishment’ in this context, is also a reference to the sceptre (ដំបង) of Brahma, through which he renders the ultimate punishment. In Hindu mythology, Brahma is the creator of the Universe.

In the Mahabharata (មហាភារតៈ), the Brahma Danda was a defensive weapon used (most famously) by Dronacharya. It had the power to neutralise the Brahmastra (ព្រហ្មាស្ត្រ) and other celestial weapons wielded by the Pandava warriors, and inflict great damage on the enemies. Therefore, in the context of Cambodian law, the Code could be viewed as a tool for retributive justice.

How do Cambodians view “justice”?

The question of how Khmers view and practice “justice” is a highly complex one and has been the subject of investigation by numerous authors and academicians who have taken the tortuous path to shed light on the culture and inner workings of Cambodian society. Instead, in this post I intend to specifically address the use of the Khmer term “យុត្តិធម៌” (/yutte-tʰoa/; Pali: yutti dhamma; Sanskrit: yukti-dharma, युक्ति धर्म) which is the closest reference to, and is often translated as, the term “justice” in the English language.

The term ‘yutte-tʰoa‘, which is a closed-form compound of two Pali lexemes yutte and tʰoa, has been defined in the 1967 Chuon Nath dictionary, the most comprehensive and authoritative lexicon of Khmer words to be produced as of date, as natural law that should be upheld (ធម៌ដែលគួរកាន់), process of being honest (សេចក្ដីទៀងត្រង់), the act of being morally upright (ការប្រព្រឹត្តត្រឹមត្រូវ).

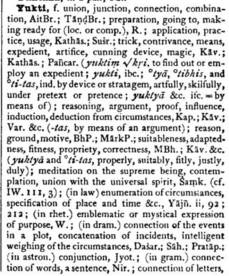

The term yutte (or yukti in Sanskrit) has been defined in the Sanskrit dictionary as a union, integration of; application, usage; [use of] reason, [act of] reasoning, induction, deduction from circumstances. Chuon Nath defines yutte as process of being right (សេចក្តីត្រឹមត្រូវ), honest (ទៀងត្រង់), as an obligation to follow the law or enactments (ការគួរតាមច្បាប់).

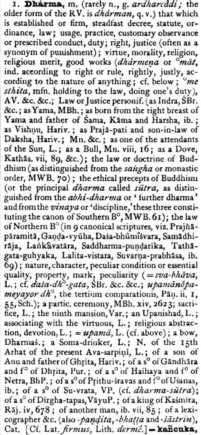

The term tʰoa (or dharma in Sanskrit) has been defined in the Chuon Nath dictionary as state of existence or nature, which governs all living beings including aspects of merit, sin, good and bad character etc. (សភាវៈដែលទ្រទ្រង់សត្វលោក គឺ បុណ្យ, បាប, សុចរិត, ទុច្ចរិត។ ល។) which is a reference to the fixed and unchanging cosmological order or natural law. This definition of dharma corresponds with the Buddhist way of thinking in philosophy.

In my opinion, the compounding words come together to mean the use of reason in a manner that is in conformity with the law of nature (or even simply, the implementation of the law of nature). This construction, however, will not be without controversy as the two terms constituting the concept cover a broad swathe across the ideological spectrum in Indic thought and philosophy.

For instance, Vajirañāṇavarorasa (1860-1921), the tenth Supreme Patriarch of Thailand expounded in “Right is Right”:

All wise men who have been religious teachers have therefore always taught men to do right. Rulers uphold Right and repress Wrong. Those who do wrong, who do injury to others, who rob others of their lawful possessions who commit adultery, or who practice deceptions, are punished, which is like extracting a thorn with another thorn. The infliction of punishment may not (in a philosophical sense) be considered a true Right; but to inflict punishment in accordance with some previously enacted law in order to repress wrong doing is called Yukti-Dharma (“Right by Usage,” in others words, “Justice”), that is to say Right by enactment, forming part of the Policy of Governance, which is the duty of a ruler to uphold. Great Monarchs naturally hold Right in great reverence and had Right as the standard leading them in their kingly ways. The Self-Enlightened Buddhas of all the three times (Past, Present, and Future) also revered Right.

On the Emblem of the Constitutional Council

The website of the Constitutional Council of the Kingdom of Cambodia is a valuable source of information on the organization of the body that has been tasked as the highest authority on the interpretation of the Constitution of Cambodia. The Khmer version of the website, however, includes a page that contains a description of the emblem (“និមិត្តសញ្ញា”) of the body. There is no translation of the text in the English language on the website. I have translated the text below to the best of my understanding.

The Emblem of the Constitutional Council (Council for the Examination of the Dharma Accord)

The settled symbols of the Constitutional Council are made in the image of Lord Brahma, the One who possesses Four Heads and Four Hands, in which he holds a collection of symbolic implements, while he sits securely on his throne. The appearance of Lord Brahma is fashioned in a manner that is fit for the One who is the Creator of the Universe.

The Four Faces of Lord Brahma are the representation of the Dharma of the Brahma Viharas [lit. Abodes of Brahma, or “sublime attitudes”] namely: Metta [‘मैत्री’, benevolence], Karuna [‘करुणा’, or compassion], Mudita [‘मुदिता’, or empathetic joy], and Upekkha [‘उपेक्षा’, or equanimity].

In his upper-left hand, he holds the Lotus Flower, which is representative of the Act of Creation. In his lower-left hand, he holds the Scriptures that represent the profound laws of the World.

In his upper-right hand, he holds a string of beads that is representative of the achievement of tranquility of the mind, ability to acquire objectives, the ascertainment of righteous action, in order to seek good deeds on the Path of Dharma, in the Ways of the World. In his lower-right hand, he holds a small earthen pot that is representative of Amrita [lit. immortality, or the Elixir of Life] that is the source of health, happiness and prosperity for the living.

(**The term ‘Dharma’ refers to Natural Law)

និមិត្តសញ្ញា នៃក្រុមប្រឹក្សាធម្មនុញ្ញ

និមត្ដសញ្ញានៃក្រុមប្រឹក្សាធម្មនុញ្ញមានរូបព្រះព្រហ្មមានព្រះភ័ក្ដ្រ៤ និង ព្រះហស្ថ៤ កាន់កេតនភណ្ឌ គង់លើបល្ល័ង្ក។ ព្រះព្រហ្ម ជានិមិត្ដរូបនៃអ្នកបង្កើ់តលោក ។ ព្រះភ័ក្ដ្រព្រះព្រហ្ម តំណាងឱ្យព្រហ្មវិហារធម៌ទាំងបួនគឺ មេត្ដា ករុណា មុទិតា និង ឧបេក្ខា ។ ព្រះហស្ថ ឆ្វេង ខាងលើកាន់ផ្កាឈូក តំណាងការកកើត ព្រះហស្ថ ឆ្វេង ខាងក្រោមកាន់សាស្ដ្រា តំណាងគម្ពីរក្បួន ច្បាប់ ព្រះហស្ថ សាំ្ដ ខាងលើកាន់ផ្គាំ តំណាងឱ្យការរំងាប់អារម្មណ៍ ការឧទ្ទិសកុសល ការចំរើនភាវនា រកអំពើល្អ ផ្លូវធម៌ ផ្លូវលោក ព្រះហស្ថ ស្ដាំ ខាងក្រោមកាន់ពួចទឹក តំណាងទឹកអម្រិតប្រោះព្រំ ឱ្យសុខសប្បាយត្រជាក់ត្រជុំ ឱ្យរស់ ។

The text in Khmer is sourced from the website of the Constitutional Council of Cambodia.

On the Khmer term for “neutrality”

As a student of the Khmer language, I am fascinated by the nuances and subtle differences which exist in the manner formal Khmer language is used to convey ideas and concepts expressed in other languages such as English and French. I will use this platform to sporadically post my thoughts on these issues. Please feel free to comment or leave your observations below.

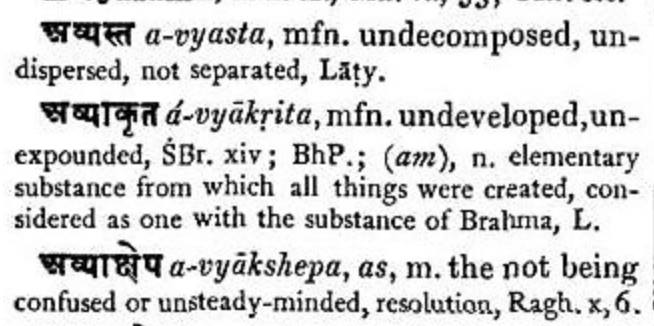

I noticed that the terms “អព្យាក្រឹត” (អ+ព្យាក្រឹត; अव्याकृत) and “អព្យាក្រឹតភាព” (अव्याकृत भाव) are usually translated as “neutral” and “neutrality” respectively, even in legal parlance. This may be problematic as the term អព្យាក្រឹត literally means “not expounded”, “not explained”, “not developed” or “not manifest”, “that which has not been put in words”.

While not exhibiting one’s views on a particular subject openly and publicly may be an attribute of a neutral entity, this term does not make for a close reference to the concept of “neutrality” itself. Conceptual clarity is essential for conveying ideas and ensuring all participants define and interpret terms in the same way.

Now consider this sentence:

“ប្រទេសស្វ៊ីសជាប្រទេសអព្យាក្រឹតមួយ។” (‘Switzerland is a neutral country’)

Interpretation by Person A: Switzerland is non-aligned, that is, it does not support or favour any side in a war, dispute, or contest.

Interpretation by Person B: Switzerland does not explain or expound its positions with respect to the affairs of other countries.

Hello world!

Hello everyone! This is my first post on the new blog. I intend to publish an assortment of thoughts on Cambodian law and practice over here. This blog is only intended to be presented as compilation of commentary on the Cambodian legal system and should not be construed as legal advice.

If you wish to seek legal advice, please consult a law firm duly registered under the laws of the Kingdom of Cambodia.